WFH: Future Path & Impact

Andrew Busch

12/07/22 | Future

WFH: Future Path & Impact

Before we do our deep dive, let’s simplify the overall environment for work from home (WFH) or work from anywhere (WFA), boiling it down to incentives driving actions.

Let’s start with the negative impact on employees from WFH. The negatives are lack of mentorship, lack of knowledge sharing and lack of interaction with management. These are important factors for all employees but have a stronger impact on younger and newer employees. These are incremental and negatively impact a worker’s productivity over time.

On the positive side, workers have learned they can have flexibility in their work schedules via WFH enabling technology. This provides flexibility in their non-work life and provides control over their time. This translates into deciding when to work, when to be available for non-work activities and how long to work during each day. WFH also increases the amount of time available for both work and non-work activities by eliminating the need to travel to an office. This can amount to a range of 5 to 10 hours per week of time recouped along with a reduction in the expense of travel. These are all powerful incentives to WFH for employees along with the reduction in exposure to COVID and flu. All of these are felt immediately by the employee.

For employers, the negatives range from the impact on workers’ productivity to reduced collaboration and knowledge sharing. These negatives are both short-term and medium-term.

For managers, the negatives are the inability to monitor employees time and the reduced ability to problem solve without coordinating schedules via communication software like Teams or Zoom. The physical separation of management and workers makes team building and building trust extraordinarily difficult if not impossible. From an expense standpoint, the employer must provide a wide range of technology to ensure the employee can be productive. Most importantly, the employer is likely paying for commercial real estate office space whose cost can’t be reduced due to longer term leases placed prior to the outbreak of CVOID.

On the WFH positives, the employers can reduce costs over both the short-term and medium term. In the short-term, they can reduce travel benefits like reimbursement for train passes or parking garages. There will likely be reduced sick time from either COVID or the season flu and reduced health care costs. Over the medium term, employers will have the ability to either re-work existing leases or greatly reduce their overall office space spend.

Overall, WFH has created both positive and negative incentives for employees and employers, creating tension between the groups.

With this as the backdrop, let’s get into the WFH weeds.

Introduction

The Work-From-Home (WFH) trend, also known as remote working, has been gaining traction in the last few years. Due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, this trend was supercharged. The pandemic, which was characterized by a global lockdown and quarantine, resulted in a paradigm shift from the 9-5 jobs and “come into the office” work-life people were accustomed to. WFH was the go-to strategy adopted by most corporate bodies to cushion the economic impact of the lockdowns on their businesses and to prevent the spread of the disease among their staff. It was a necessary preventive measure, and it worked.

As vaccines have decreased the spread of the disease and shutdowns are no longer an appropriate response to the outbreak, the WFH trend has maintained its popularity as many employers and employees, who have experienced the countless benefits of working from home, are reluctant to go back to their pre-COVID schedule. For many workers, WFH is now the preferred structure, while for many employers, total WFH is not. A hybrid model is now evolving with some combination of work at home and work in the office.

This article outlines the past, current, and future state of the Work-From-Home (WFH) trend and the factors influencing it.

WFH Prior To COVID-19

Working from home was not unheard of before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a report by the International Labour Organization (ILO) published in 2020, about 7.9% of the global workforce worked permanently from home. While 52% of workers on a global scale worked remotely at least once a week before the pandemic.

A higher percentage of home-based workers were mainly found in lower-middle income countries and worked as self-employed business owners, artisans, and industrial home-workers. The rest of the estimated population was from high-income countries and was dominated by teleworkers.

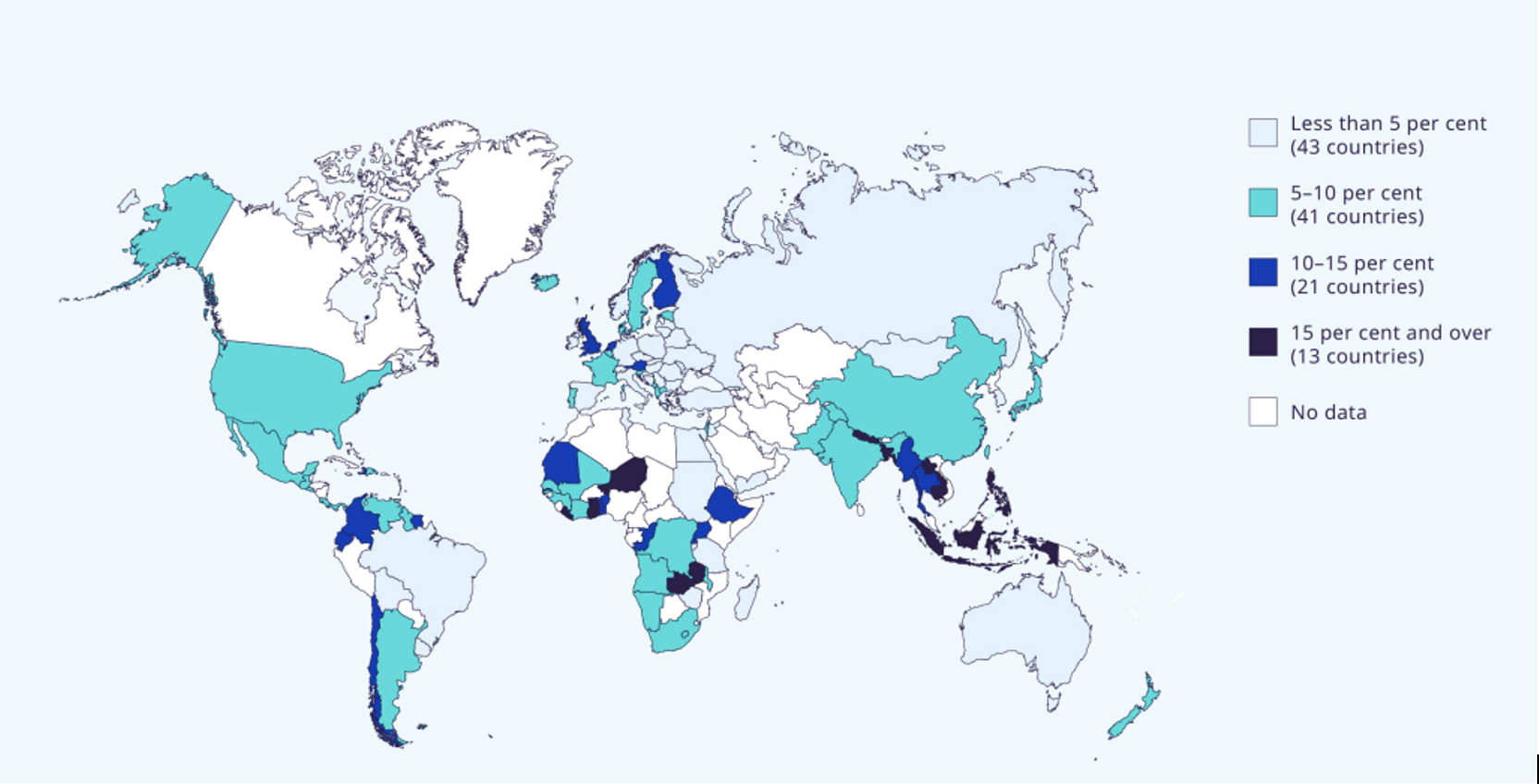

The map below represents an estimate of workers that worked remotely before COVID-19 based on a survey from 118 countries (which represents about 89% of global employment).

Source: International Labour Organization report.

Working from home was more common among Gen Z (1997- 2022), who are more tech-savvy as they are digital natives. Given these skills, Gen Z could transition to WFH easier due to their familiarity with technology like video conferencing (Zoom, Teams, Facetime) and their dexterity with communicating via text, chats and email. Broadband internet adoption also played a major role in facilitating rapid communication. The Millennials (1981-96) also have knowledge and experience in digital technology, which has enabled them to be slotted into the remote working system ecosystem. The Boomers generation (1946-64) was less inclined to technology, and fewer were comfortable working from home.

WFH During the Pandemic

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic came a dramatic change in how the world operates. Globally, governments shutdown large sections of their economies to reduce the spread of COVID. The service sector experienced the largest negative impact as many jobs were deemed non-essential like restaurants, bars, travel and retail. Other sectors were deemed essential like utilities, healthcare, transportation, and grocery. For the nonessential sectors this resulted in a necessity for an operating system that ensured continued productivity without putting the workers at risk. This led to the adoption of Work-From-Home, a.k.a., Work-From-Anywhere (WFA) or remote working by many organizations. Organizations with no intention to embrace remote work had to make way for it, and those who already operated partly remotely had to embrace the system. The digitization of small to medium-sized firms was greatly accelerated. Clearly, it was a case of “adapt or go out of business.” According to a report published by the International Labour Organisation in 2020, during the second quarter of the year, 17.4% of the world’s working population worked from home, which accounted for an estimated 557 million workers. The estimated number of people that effectively worked from home in some countries was documented in some reports as follows;

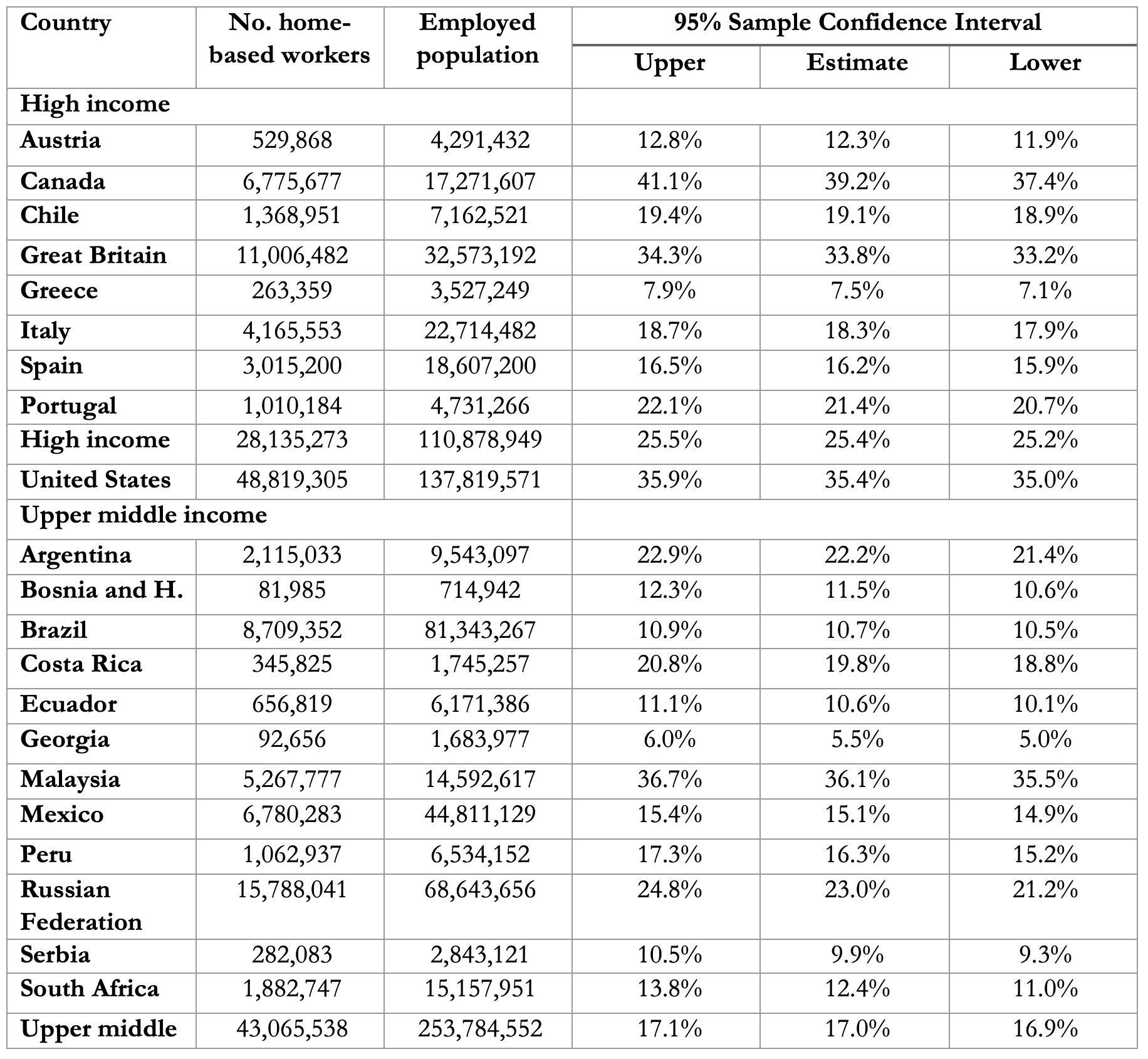

Barreo, Bloom, and Davis (2020) estimated, using CPS data, that 37.1% of workers in America worked remotely during the pandemic. Felstead and Reuschke (2020) concluded that 43% of workers in Britain effectively worked from home. Gottlieb et al. (2020) estimated the number of remote workers in Brazil and Costa Rica at 11% and 13%, respectively.

The table below is an avid representation of the estimated number of persons that worked remotely across 21 countries, according to the International Labour Organization report.

Impact on Employees

According to the Pew Research Centre Analysis of Monthly Labor Force Data, the number of Boomers that retired in the year 2020 drastically increased compared to the previous years, with a record of 3.2 million more Boomers than the 25.4 million recorded in the same quarter in 2019. This was because workers between 50 and older find it difficult to re-enter the workforce after being unemployed, and many chose to avoid the risk of getting COVID if they returned to work. The retiring Boomers were more common in Asian American, North-eastern, and Hispanic countries.

The pandemic also lessened the chances of Gen Z pursuing college degrees. A survey by the ECMC Group reported that nearly one-third of the respondents surveyed responded that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their finances to attend college. 27% reported a change in post-high school education plans due to COVID-19. Many of them had begun to think that a college education was not worth the funds or time it required. They wish to forge their educational path and believe success is attainable without a college degree.

Impact on Employers

The COVID-19 pandemic also affected businesses. Many companies either had to shut down, lay off most of their staff, or suffer severe financial distress. According to the New World of Work Survey published in August 2022, about 12% of businesses globally shut down, although some were temporary. More than a fifth of the respondents reported laying off their employees. Companies in manufacturing and hospitality were more able to follow the path of layoffs. At the same time, those in the education and healthcare industries had to find alternatives. Businesses had to adopt more flexible methods of getting work done. 56.5% of respondents from the survey stated that they were shifting to remote work, and 59.3% stated travel reduction was their next move. Another 44.9% stated they were making plans to adopt a more flexible work schedule, and 44.1% stated redesigning the working environment was their suitable alternative. Many had plans to increase their sanitation protocols, personal protective equipment, and overall employee safety. The New World of Work survey confirmed that nearly 62.6% of respondents stated that their businesses had to go fully remote, and 32.3% had to redesign their work to encourage a partly-remote environment. The COVID-19 pandemic indeed caused an unexpected yet necessary transition to remote working environments that allowed employees to work from anywhere.

Employers embraced technology that facilitated remote communication. All tech companies in this space saw dramatic increases in sales and users. Zoom became the poster child of remote work due to its low cost and user-friendly tech. Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Slack are all examples of technology that allowed individuals, companies, classrooms, etc., to meet virtually, communicate, and learn during the pandemic.

WFH Today

According to the “Working From Home Around The World” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, published in 2022, “the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a huge, sudden uptake in working from home, as individuals and organizations responded to contagion fears and government restrictions on commercial and social activities. The pandemic forced businesses to adopt the Work-From-Home system massively. This adoption caused lots of new information about the workability and effectiveness of Work-From-Home to be derived. This was especially so because working from home had to be experimented with simultaneously by producers, suppliers, consumers, and the commercial network at large.

Over time, it has become evident that the big shift to work from home will endure after the pandemic ends.”

Working from anywhere (WFA) would have been nearly impossible a couple of years back. Still, with the advent of technology and software in recent times, it is more practicable and has been adopted by many organizations.

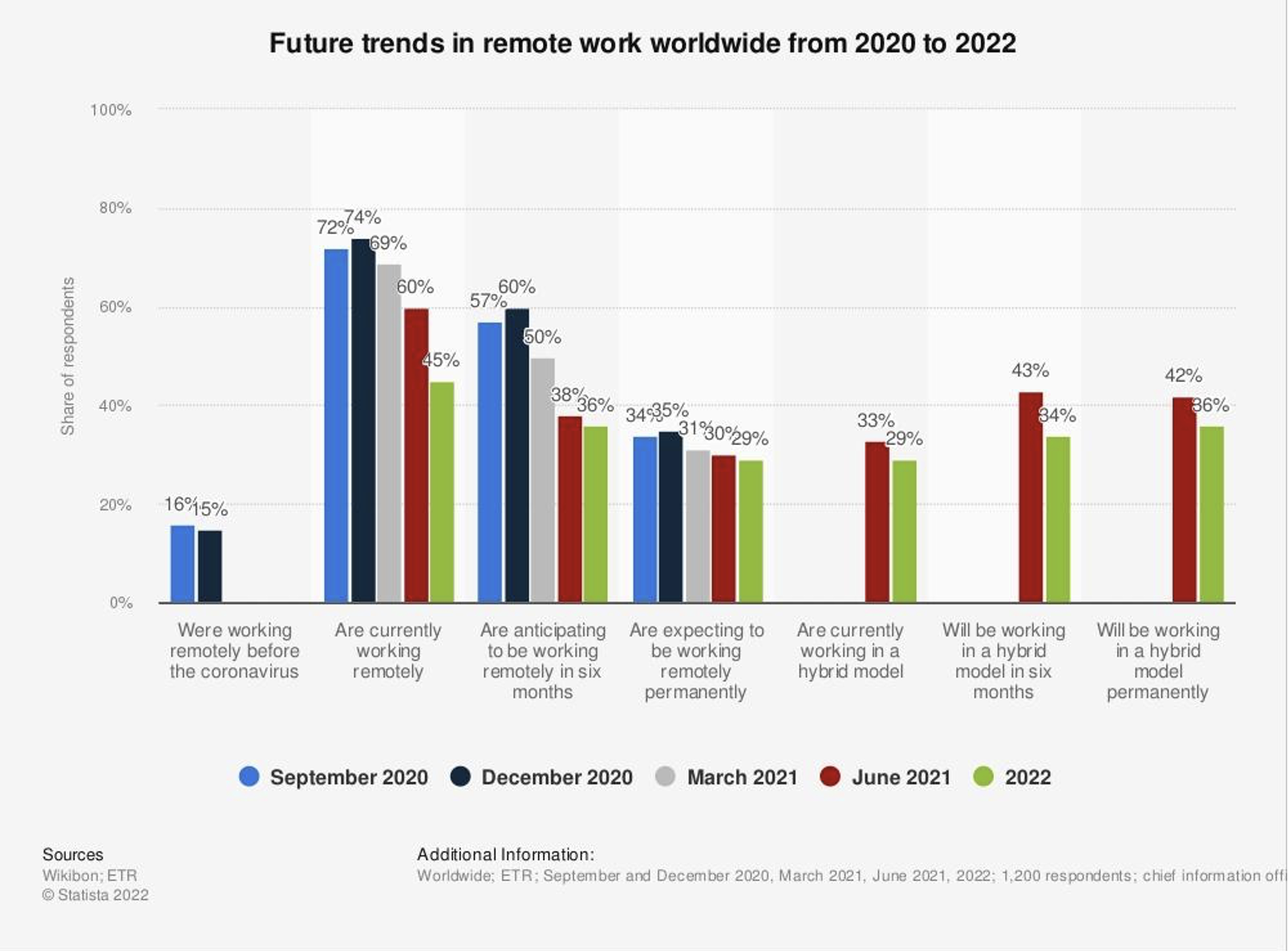

The figure below shows an analysis by Statista on the remote and hybrid work trend from September 2020 to 2022.

Although from an employee’s standpoint WFH might appear fantastic, it is not entirely the case. Yes, many employees have reported increased productivity and flexibility in their work schedules. Still, Work-From-Home does not mean less work, and it is only partially favorable for all employees. Some employees also reported an inability to disassociate personal life from work life. There are distractions for those who do not live alone or have designated workspaces. Some of the challenges being faced by organizations, businesses, workers, and the economy at large, as concerns the Work-From-Home (WFH) system, include; conflict between employers and employees, labor shortage, inability to mentor or transfer knowledge from older workers to younger workers, hollowing of central business districts and commercial real estate in major cities.

Conflict Between Employers and Employees

Remote work has projected conflicts between employers and employees globally. This is due to multiple factors, such as the inability of many employees to focus on the work that needs to be done. Working from home comes with many distractions compared to working in an office. Several employees need help to handle these distractions. They may not meet up with deadlines or get work done as quickly as expected. Another factor that causes friction is the inability to communicate well. Although there are many virtual meeting platforms for audio and video conferencing, they serve a different energy than a physical meeting. There might be an inability to connect on a personal level or issues with relaying information, which could eventually cause friction between employers and employees. Finally, there is the monitoring of remote employees and software tracking of activity that can lead to distrust on both sides.

Labor Shortage

For companies requiring physical labor or presence, remote work cannot function effectively. These were the industries that were majorly affected by the global lockdown. A lack of adequate on-site employees meant an inability to produce or distribute substantially; this affected businesses’ ROI and revenue. Compounding the labor shortage problem, more people retired than expected. According to Miguel Faria-e-Castro, a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, roughly 2.4 million additional Americans retired in the first 18 months of the pandemic than expected, making up the majority of the 4.2 million people who left the labor force between March 2020 and July 202. Another factor increasing labor shortages is the closing of the U.S. border with Mexico. As well, the Gen Z demographic cohort for 20–28-year workers is smaller than the Millennial cohort. The number of Americans aged 18-64 (labor force available) rose only by 0.2% from November 2019 to November 2022. What rose dramatically was the number aged 65 and older. It increased 7.2% and is likely the culprit for decline in labor force participation adding to the labor shortage. Finally, the lack of affordable housing and affordable day-care have reduced the number of available workers in both urban and rural areas.

Inability To Mentor New Workers

According to Live Career’s 2021 Study, half of all remote workers agree that they do not get as much feedback remotely as they do on-site. Working from home creates a barrier that prevents adequate mentoring of new employees by the older ones in the business. This is disadvantageous to the new employees, who might not be able to pick up valuable skills, and disadvantageous to the company because the new employees, who are the company’s future, might need help upholding the standards. It also sets up pressure on WFH employees to come into the office to compete with on-site workers who interact with upper management more often.

Hollowing Of Central Business Districts

Since employees will be working from the comfort of their homes or anywhere they choose, companies will no longer need to acquire large office spaces. This will affect commercial real estate and cause a hollowing of central business districts (CBDs), which has important implications for the economy and debt related to office space. CBD businesses, like restaurants and copier centers, are negatively impacted by the lack of customer traffic. As these businesses close, many buildings lose tenants, and the negative feedback loop toward commercial real estate accelerates. San Francisco, Chicago, Seattle, Los Angeles and New York have all seen declines in occupancy and prices.

WFH Future

Where Do We Go from Here?

Stats and recent occurrences project that remote jobs are not just here to stay in the short term. According to Owl Lab’s 2022 State Of Remote Work Report, currently, 16% of Companies are fully remote. The report also states that 1 in 2 people working in the U.S. won’t return to jobs that don’t offer remote work after COVID-19.

Also, according to the Future Workforce Report by Upwork published in 2020: by 2028, 73% of every workplace team is expected to include remote workers. This, coupled with the fact that it has been reported that 69% of millennials would rather give up on certain workplace benefits to work from home, makes it all the more evident that the work-from-home trend is going to be with us well into the future. This reflected the mood of the times during COVID and likely overstated the case for WFH/WFA.

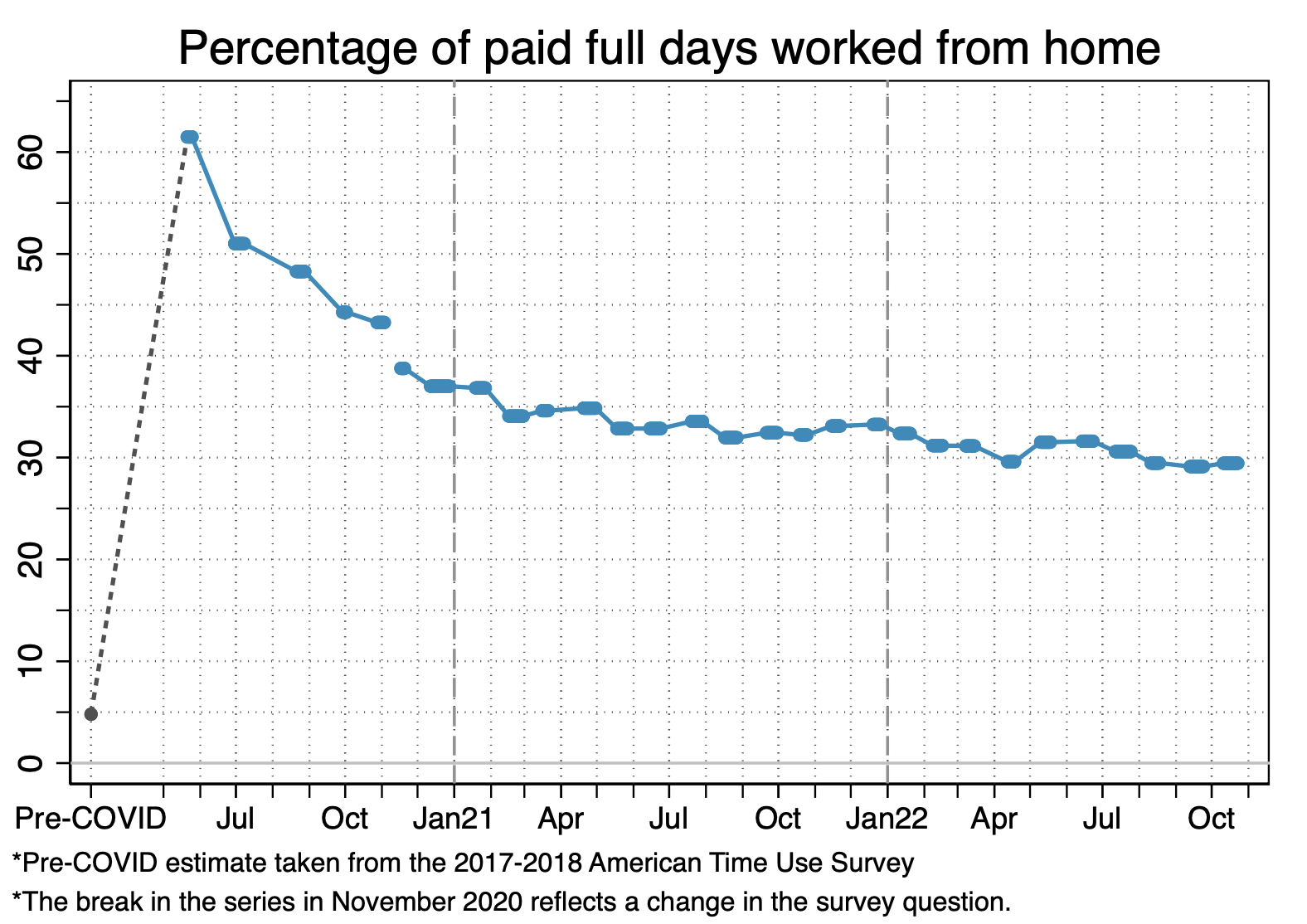

Source: WFHresearch.com

Recent surveys show 30% of days worked are from home and this is holding steady since April. (See Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, 2021. “Why working from home will stick,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731.)

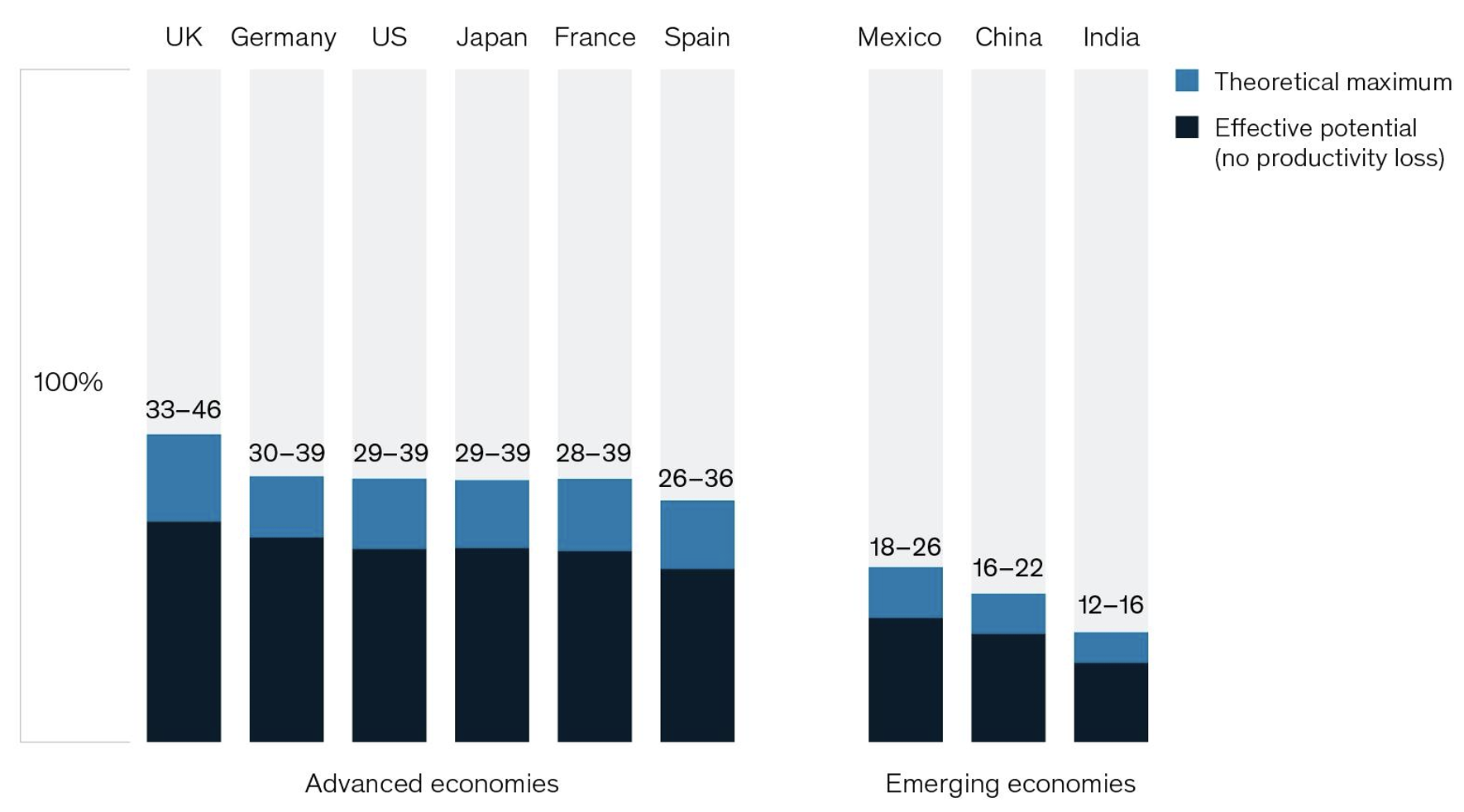

It is important to note that the trend has varying degrees of success across different economies. McKinsey Insights reported that remote work is more likely to thrive in advanced economies than in emerging economies. Figure 2 below shows the potential share of time spent working remotely in advanced economies and emerging economies.

Source: Mckinsey future of work review.

In summary, the genesis of remote work existed long before the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, the pandemic caused Working-From-Anywhere (WFA), a.k.a. Working-From-Home (WFH), to accelerate dramatically. Subsequently, more information about its practicality and effectiveness has been discovered and utilized to overcome COVID shutdowns. In the short run, the developed world appears to be tilting towards maintaining some portion of a remote work system as companies attempt to attract new workers while simultaneously attempting to overcome the downside of a remote workforce. For the next 2-5 years, a hybrid model is likely with a structure of 3:2 or 2:3 days in the office and days working remotely. This structure has serious implications for central business districts, commercial real estate and the economic health of major US cities. NBER research stated, “Physical office occupancy in the major office markets of the U.S. fell from 95% at the end of February 2020 to 10% at the end of March 2020, and has remained depressed ever since, only gradually creeping back to 47% by mid-September 2022.”

The longer labor shortages persist, the higher the likelihood workers will have the ability to demand WFH or switch to companies that provide it. The longer WFH persists, employers will be able to reduce their office space footprint, reduce their overall costs and increase the permanence of the work structure. This has the potential to push central business district demand down further while potentially pushing up demand outside of the area to where WFH workers reside. Another serious disease outbreak would accelerate this trend.

However, keep in the mind the history of disease outbreaks. The initial reaction of the population is to try to get away from the outbreak which is usually in a large city. This spreads the disease to other cities and increases the migration pattern. Yet, history also shows that these trends are eventually reversed as the disease dies down and the benefits of living in large cities are re-evaluated. Today, the unknown is how long this process will play out and how technology has altered the calculus.